Deconstructing Deconstructivism.

Deconstructivism, another theory critically aimed at the norms of culture, is a theory that has impacted all of us and yet, most of us have never heard of it. To understand it is, at best, to attempt to understand it because, be warned, it is ambiguous and vague. It is like nailing Jello to the wall; once you think you understand it, it interacts with something else and changes. Deconstructivism is change and difference and criticism and tension all rolled up into what I see as varied disparity. It first appeared in a 1967 book entitled, On Grammatology, and has grown in reference and documentation ever since.

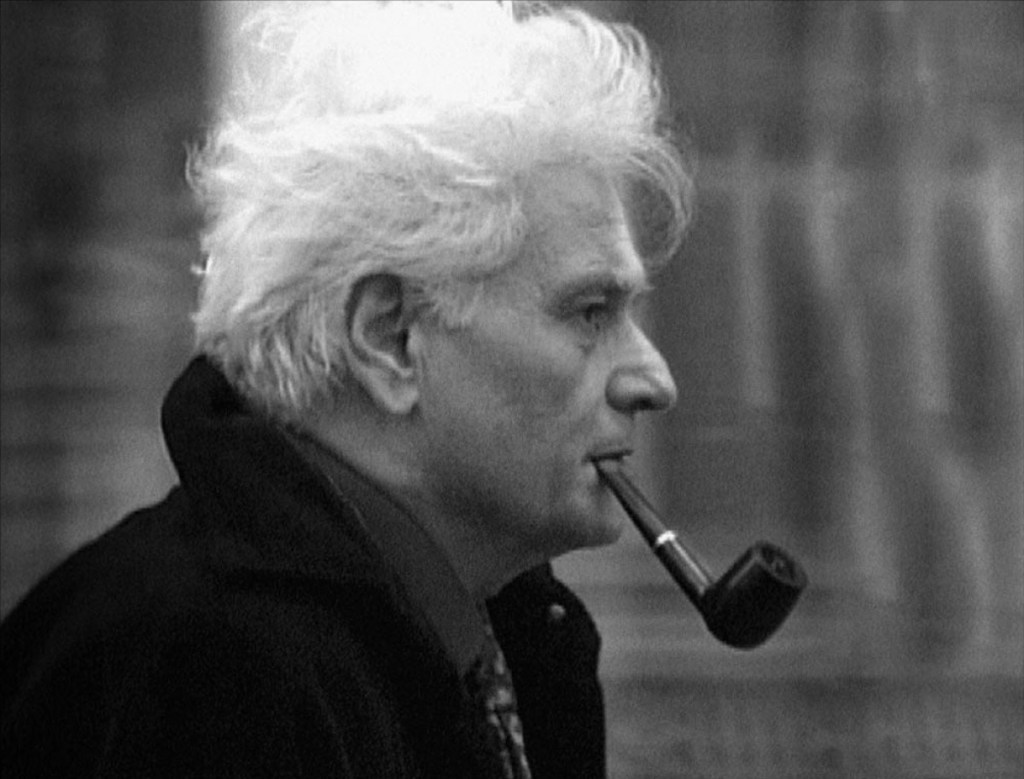

Let’s begin with a quote. Jacques Derrida, in his article, Letter to a Japanese Friend, explained deconstructivism to his friend by insisting that it is “an event that does not await the deliberation, consciousness or organization of a subject or even modernity” (Derrida, 1985, p.2). If this seems a rather odd way to describe an event, you are right, but it is not an event that he is describing; it is deconstructivism. Inside that seemingly innocuous description is affirmation to deconstructivism’s metaphysical reality. Derrida stated to his friend (Professor Izutsu) that to define it or even translate the word “deconstruction” would take away from it, which is a suggestion to its nature and to its protection. How does one disagree with that which cannot be defined or translated? The answer is simple: one does not because one cannot.

Derrida, in my opinion, was stating that deconstruction was a notion of a reality rooted in situational agency. It was designed to avoid the confined corner; to avoid the proverbial box or the closed door and to assert its own agency in interaction with individualism (or context) as a means of truth. According to Derrida, it was and is a critical methodology that analyzes how meaning is organically constructed and deconstructed within language, which we all understand to be the primary means of communication between human beings, and yet it is not language that seems to be under attack. Instead, language seems, to me, to be the vehicle of delivery for deconstructionism.

Let’s be clear; deconstructivism is not a form of Marxism nor of Critical Theory, but it is related to both, although indirectly. The process itself claims to reveal the instability of language, which it presents as language’s true and natural state. Is language unstable or is language, as my cynical mind suspects, being pushed to instability by deconstructionism? I would like to posit a question: if instability were not language’s true and natural state, could deconstructivism determine language’s state or would it, instead, change its state? I am not sure, but I look forward to exploring that possibility and others. I do know this; its existence depends on instability of language and meaning.

Back to this question, is language unstable? Yes and no! I think language is like anything else; it works from instability to stability. I know I seek clarity in my communication and one of the ways I do that is to ensure that meaning is consistent with those with which I am communicating. How is language unstable? I believe language is unstable if meaning inside language is unstable. How does that instability remain and not work towards stability? One of the methods of maintaining instability is through addition. When other meanings are added to true meaning, clarity is not produced but instead, instability is maintained. Addition, for me, creates instability, especially when it comes to language. If we have found instability as a state of language and this discovery was the direct result of deconstructivism’s interaction with language, then, there is another more difficult question to consider. Is the instability of language its true and natural state or is it a direct result of deconstructivism’s interaction with language?

Deconstructivism claims that one of its goals is to push meaning to its “natural” limits and expose its “true” nature which, according to Derrida, is instability heavily dependent on difference (addition). I am not a big fan of coincidences and see them as problematic. Here is my issue. If language is considered unstable in its natural state and deconstruction is instability in its interaction with language, is this a coincidence? Again, I don’t really buy into coincidences. I do know that when instability interacts with stability the results will generally be less stability. We know this through the study of physical systems, biological systems and even social systems. We also know instability manifests in three ways: gradual change, sudden transitions and oscillations, and there is nothing to indicate that when instability is introduced to a stable system, that stable system stays the same or even stays stable. It always changes; at times, stability may eventually be achieved again but not before the system goes through a period of instability. My point is that I am not convinced that the natural state of language is instability. There is a solid case that the instability of language is due, in part, to its interaction with that which is unstable. Are you confused yet? Buckle up because this roller coaster ride is just beginning. This post is the start of a deep dive into the world of deconstructivism. Stay tuned for my next post in this series. Until then …

Derrida, Jacques. (1988). “Derrida and difference.” (David Wood & Robert Bernaconi, Trans.). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. (Original work published 1982).

Discover more from Bridge Roe: Where Thinking Matters

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.