Part VI: Living an Existential Life

With existentialism being so abstract, how does one live inside its philosophy? This is the last question I will tackle in this series in this last post.

I begin with a quote from Le Monde, a Parisian newspaper who attempted to define existentialism in 1945. In their December edition, they admitted that “Existentialism, like faith, cannot be explained; it can only be lived.”

A few posts back I referenced that it is indeed more a faith than a philosophy. Why is that? One of the main reasons is that it bases conduct on a belief in individual freedom more than anything else. One is free to choose one’s own conduct, but here is the difficult part, inside that freedom there is a belief that no objective moral order exists independent of the human being. It is up to each human being to create his or her own moral order by way of living it and affirming it through their own authenticity as they live. I don’t know about you, but that seems a bit daunting.

Existentialism, you could say, is obsessed with individual authenticity—how individuals choose to live their lives. It rests on some bold ontological speculations, about what does and does not exist. One of the weightiest speculations is the belief that there is no god or entity outside of the human being; therefore, moral values do not exist outside of the human being. There are no moral absolutes nor are there universal laws or codes of ethics that apply to all of us. Values come to us as we live our lives in authentic ways. If we live our lives as if values were given to us by God or existed outside of our being, that would amount to existential sin: it would equate to living a life refusing to face the freedom you have been given to live your own authentic life, but from where does that thought come? Is it even a valid thought if it comes to us from others? You can see the dilemma we face. This individual authenticity, it is very important to the existentialist.

Inside an existential world, every individual is responsible for deciding, on their own, how to evaluate their choices, and it is only through those individual choices given to them by the individual freedom they have that values come, but do they? An existentialist believes that it is the action rather than the principle that creates value but is the action not principled action, especially if it applies only to the individual. To value one action as more important than any other action is to prioritize it—to set it apart as an ideal, which is value, is it not? That ideal is what we strive to achieve as we live our lives. In existentialism, it is authenticity; in the Christian faith, it is the glory of God. Is there a difference? When we choose to act in a certain way, we are choosing what we think is the right as it applies to us. Inside existentialism, we are to live for ourselves; inside Christianity, we are to live for others. The only difference is the direction; in existentialism, all actions are directed inward to self, but inside Christianity all actions should be directed outward to others.

Existentialism, as we have referenced, does not believe human beings have a pre-existing nature or character, but in many ways, it instills this belief as an existing nature. We are “existentially” free to become “self-created beings” by virtue of our actions and our choices but is that not an existing nature that must take hold of us for us to live as existentially-free individuals? We are told that we possess absolute freedom … that we are free to choose and this truth is so self-evident to us, or it should be, that it never needs to be proven or argued. Again, is that not a pre-existing nature or maybe the better word is condition.

There is acknowledgement that no one chooses who they want to be completely. Even Sartre recognized this and he also recognized that each person has a set of natural and social properties that influence who we become, which we might refer to as social conditioning. He gave them a name, “facticity.” Here is where, in my opinion, essentialism gets a little upside down. Sartre thought that one’s facticity contained properties that others could discover about us but that we would not see or acknowledge ourselves. Some examples of these are gender, weight, height, race, class and nationality. There are others but it was thought that we, as individuals, would hardly every spend time examining these ourselves and yet, today, many spend all their time lamenting them or agonizing over them. An existentialist would describe these as an objective account not capable of describing the subjective experience of what it means to be our own unique individual. As we look out at our world, what we see is the breakdown of not only society but of existential philosophy.

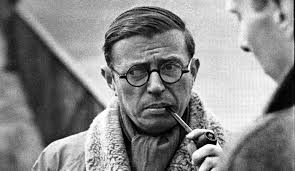

Existentialism came to age between the years of 1940 – 1945, during and after WWII, which was a unique time, especially when considering the views of freedom and choice in Europe at the time. Europe, at this time, was, in my opinion, the perfect storm for existentialism to blom and grow. Its focus on individual freedom was so very appealing to those coming out of war-torn Europe who had lost all freedoms for many years. The appeal was every bit as emotional as it was intellectual. Sartre was quoted as saying, “If man is nothing but that which he makes himself then no one is bound by fate, or by forces outside their control.” He was pushing the idea that only by exercising personal freedom could people regain the civil liberties they had lost, which, was taking advantage of the situation and the state of those coming out of the war having lost everything.

There is a problem and a price to be paid for the freedom to do whatever you want when every you want, which existentialism advocated, and that price was steep. In such a culture, everyone gets to have that same freedom, even those who oppose your right to freedom. Coming out of a war that took everyone’s freedom, individual freedom was embraced and even needed to repair and restore, but with came a burden that we are no just realizing. There is really no such thing as individual freedom unless you live alone on a remote island. Any type of freedom, especially one advocating that every choice that is ours is ours alone will eventually affect others. There is just no way around this.

In the situation coming out of a long war, the burden was light as our individual choices were directed at restoring those individual freedoms lost, but eventually those individual freedoms would move beyond our own individual freedoms and seek other things beyond us. The desires would extend beyond what we had and seek what we were owed and what we deserved. It is in those times that this light individual burden became heavy and hard. Sartre recognized these times and presented an explanation. He said it is in these hard times that we adopt a cover of sorts to escape the pressures of choices that extend beyond us, which he called those choices “bad faith.” He said that we used “bad faith” when the pressure of choice was so overwhelming that one pretends there was no freedom after all. Sartre would say that this is a special kind of self-deception or a betrayal of who one really, but there is also evidence that this “bad faith” was a personal betrayal of existentialism. It was a desire for more … more freedom … more liberties and more rights. Sartre would claim that this “bad faith” was merely a denial of the freedom afford to us, but who will deny freedom? He claimed that one common form of deny one’s freedom was to present excuses for one’s behavior, but is not an excuse presented in a situation as a means of justifying a wrong action knowing the right one? Again, this is another sizable hole in existentialism.

As I close this series, let me summarize the main tenets of existentialism and present a few questions to consider in response to each.

First, true existentialists believe individuals should embrace their own freedom, and that everyone has the freedom to make their own choices and these choices will and should define who we are. The problem with individual freedom, as I have referenced, is that it often comes at the expense of someone else’s freedom, unless, again, one lives as a hermit or in paralysis. The other issue of freedom is this one: There is no such thing as individual freedom. Everyone lives in some sort of community where are choices infringe upon others, which makes most of our choices not individual.

Second, true existentialists acknowledge the absurdity of life. They believe that life is absurd and devoid of inherent meaning which, for them, prompts individuals to create their own meaning and values through their own choice, but is this absurdity pre-existing either in culture or as a thought? It is presented as ever-present which is pre-existing unless it comes from the individual living freely in a world where everyone is living their own different life, which does make absurdity a reality. My question is this, does this individual freedom contribute to the absurdity or create it?

Third, true existentialists believe in accepting responsibility for one’s own actions. They believe, and rightly so, that with freedom comes responsibility and one should own one’s decisions and the consequences that come as the result of them. They believe doing this will empower one to live authentically and with integrity, which I am in full support of living with both, but the question is will living an existential life produce both? What we have seen is that living authentically does not necessarily lead one to live with integrity, which also suggests something else is involved in life. In most cases, integrity never reveals itself in isolation as there is no opportunity to put it in practice. Most of the time we put integrity into practice in our interactions with other when we place them as more important than ourselves. How can we do that if living our best existential life is to live an authentic individually-free life?

And, finally, true existentialists believe in living authentically at all costs. They strive to be true to themselves and to avoid conforming to cultural or societal expectations and norms. The key to authenticity to an existentialist is to understand one’s desires and values and live in accordance with them to the best of one’s ability. This is existentialism, but is it, really? As I have pointed out there are some real issues of consistency and causation that must be addressed to make sense of this world in which we live, whether we are existentialists, Christians, atheists, agnostics or aliens.

As I close, the idea of existentialism tends to scare most when they hear the term, but the reality is that it is another philosophy trying to make sense of the world in much the same way we are. At the end of the day, I think we all want the same thing … for the world to make a little more sense to us than it did yesterday. I hope this has been a fruitful experience for those who have joined me on this journey. I hope this has pushed you think a little deeper and to spend a little more time considering different thoughts. I hope you don’t see difference as threat, but as that friend that sees the world differently than you do. You may not agree with him, but he makes you better because he pushes you to think about the things you want even stop and think about with his prodding. Difference is not something to be afraid of if you can think. This why thinking matters … always! Blessings!