Deconstructing Deconstructivism: Part IV

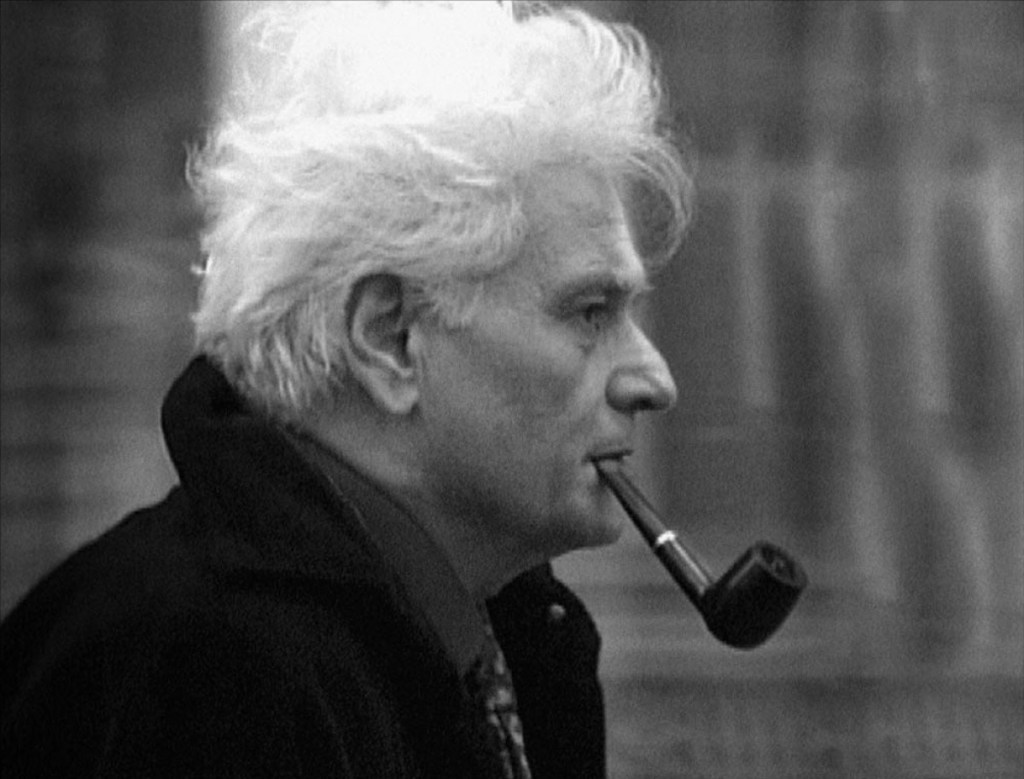

We have examined deconstructivism, but there is one question that remains: how are we to respond to it? I would suggest that any response begins by, first, coming to an understanding of instability as it is defined by deconstructivism. There are questions that come with any speculation of instability as an organic state of language. What if its organic state was, instead, something else? What if instability was merely the tension of determination? Derrida provided some support for this type thinking when he referred to the openness of instability as “aporia,” describing it as a puzzle or quandary (Jackson & Massei, 2012). What if “aporia” was that which was imposed over meaning by deconstructivism? Nothing is for certain and should not be thought of in those terms.

Let’s begin this post, instead, with some hard truth; instability is a part of life, but it is a part of life we fight against. No one wants to be unstable, even when it comes to language. We seek clarity not confusion, especially in our communication. What do we do with confusion? We look for ways to clarify it and eliminate it, and yet deconstructivism seems, to me, to seek to keep it. I see it seeking to be the means of clarity. Do I dare go further? I think it goes beyond clarity and seeks to be “the” means of meaning. What other purpose would it have for keeping instability alive, especially in language? Let’s back up a bit and look at what instability does, if left on its own. Simply, it destroys stability. As we have studied deconstructivism, we have referenced its interaction with norms. Instability undermines stability, especially when it comes to stable norms. Derrida advocated that an important part of the process of deconstructivism was to keep asking questions, which is a theoretical device used to keep meaning and language from falling into a sameness, which is never seen as a critical tool of analysis or as positive. Sameness is never welcomed in critical analysis and always viewed with suspicion and as bias.

Derrida saw both language and thought as living in what he called binary opposition, which he suggested was a confirmation of the instability of language. He saw language relying on opposing concepts like good/evil, true/false and happy/sad to sustain itself. He did not see these as part of the natural state of language but as constructions imposed on meaning and language by human beings. What is language if not a tool of communication for human beings? I do not see language as entity unto itself; I see it strictly as a tool used by human beings to communicate. In my reading of Derrida, I did not get the sense that he saw language in the same light as I see it. He saw these binary oppositions as existing within a dangerous possibility: that one term would be given the privileged status over the other term, thus affecting the natural state and balance of language. He claimed that this privileged status (one term over the other) prevented meaning from “disseminating out beyond its initial intended meaning” in multiple directions, which assumes language is not a tool but an entity unto itself. One question I have regarding binary oppositions is this one: do they not define each other? Is not dark the absence of light? Is not false the answer that is not the right answer? What is the alternative if these binary oppositions are removed? I don’t see them as constructions of human beings but instead, as observations of human beings. Human beings did not create dark or truth or even good. They observed its presence or its absence through, in many cases, its binary opposite.

When it comes to communication, I do not seek to protect two binary opposed meanings, at least not when I am seeking to be clear in my communication. Communication, for me, is determining shared meaning for the purposes of effective and clear communication. It is understanding meaning and embracing the same meaning. Did Derrida see language impacted by context or was he afraid of the impact of context? I am not sure. Derrida claimed to have seen language and thought as indecideable (his word), a term he used to describe meaning as having no clear resolution, which, from my perspective, leaves language in one place … in a state of confusion, which could also be referenced as instability. Is this what he saw or is this what he needed language to be for deconstructivism to grow and thrive? How we see and respond to deconstructivism will do one of two things: it will either feed it or starve it and kill it.

Deconstructivism if often referenced with terms like unpacking, destabilizing and undermining in regard to its interaction with norms, which it would define those that are stable as assumptions, as binaries and as privileged. These are intentionally negative terms designed, in my opinion, for them to be unpacked or destabilized. But, again, what if the theory of deconstructivism is wrong when it comes to norms? What if instability is not a natural state but instead, one created for the purposes of destabilizing those norms that are stable? If this is the case, then we would need to confirm through a dialectic method whether deconstructivism is viable or not. When it comes to literary theory, deconstructivism operates in literary theory by encouraging us to read literature closely but with skepticism, questioning binary oppositions, resisting final interpretations and embracing ambiguity. When we put all these words together—skepticism, questioning, resisting and ambiguity—what do we get? These words encourage doubt, challenge authority and embrace uncertainty, which could be summed up in one word, instability. The question then becomes does deconstructivism identify instability or produce it?

Considering this question, I think we must, first, understand deconstructivism for what it is. I am not advocating that it produces instability, but I am say that there does exist a possibility that it does. Therefore, we cannot assume that it does, nor can we assume that it does not. It is important to understand that any disagreement with its principles—its skepticism of fixed meanings, rejection of absolute truth and tendency towards destabilizing established frameworks—if not done critically and constructively will be engaging it in the very manner being criticized and result in confusion or ambiguity, which is exactly what deconstructivism wants and, in many ways, needs. In this series, I have tried to provide a picture of this theoretical position from different angles for the purpose of understanding. Ignorance is offering criticism of that which we do not understand without understanding; analysis is offering constructing critical analysis in a thoughtful, respectful and knowledgeable manner. Back to our question, how do we respond to deconstructivism?

Let’s begin by seeking to understand what we believe and subjecting our own beliefs to the same analysis to confirm whether our beliefs are true or not. So many of us are unwilling to do that but must be willing to do that if we are seeking truth. We must, next, understand that our perceptions, as right and as true as they feel, are only our perceptions. They are not reality or even true, at times. Sometimes they are true and other times they are not. Most of the time they are built and re-enforced by someone else’s perceptions, which should be analyzed as well. For example, I have been advocating in this series in subtle ways that one of the weaknesses of deconstructivism is its lack of focus on the pragmatic reality of communication. To communicate, we need “shared linguistic and cultural frameworks,” and my example of that is language. English speakers do not communicate well in other parts of the world if they are monolingual or unwilling to engage in the language of the region in some way. If they expect everyone to speak English and have a very superficial view of communication, then they will struggle to communicate because they are allowed instability to reign and seek no action to clarify. There are other aspects of communication like culture, attitude, countenance and a willingness to engage and communicate. If none of these are engaged, communication will be lacking and remain ambiguous and confused. That sounds nothing like the state of communication needed to effectively communicate, and yet, that is a practical example, albeit simple, of deconstructivism at its simplest level.

As we engage deconstructivism, and you will engage it, it will be helpful to you to recognize it. How will you do that? Let’s start with its tendency to blur all distinctions. Not only will it seek to destabilize stable norms, but it will blur clear distinctions which tend to lead to relativism, which is another sign of the presence of deconstructivism. Where do we see this? Right now, the most prominent place we are seeing this is in the blurring of the genders, male and female. This is clear indication of the presence and the impact of deconstructivism, but it is also an opportunity to address deconstructivism’s weakness when it comes to practicality and real-world applications. While there is a blurring of the genders (per deconstructivism) there is not a blurring of the product of this burring, which is contradictory and an opportunity to determine its validity that we need not miss. Again, our response depends on our ability to identify the presence and impact of deconstructivism and then respond respectfully and lovingly to it inside its own theoretical methodology. This means we must understand it, something most of us are unwilling to do. It is helpful and intelligent to read and study both sides of an issue. As difficult as this is to do, to really understand and respond well, we must do this. Another tendency of deconstructivism is its push towards ambiguity, which is not applicable in several vocational situations, especially in areas like medicine and engineering. We should not blindly and emotionally reject deconstructivism outright because of these two examples but use them by applying them back on top of deconstructivism as a means of pointing out weaknesses, gaps and breakdowns and asking questions.

Deconstructivism is a critical theory that is used in academics effectively in micro-situations, but its struggles, like most academic theory, begin when it is applied in culture in real-world macro-situations or used to push an agenda and change behavior. Any theory, good or bad, if applied in similar situations, will produce similar results. We should respond as civilized respectful human beings with a critical eye towards its application in wrong settings to learn more about it and use it to pursue truth. In the right settings, it is effective in rooting out bad theory and paving the way for good theory, but in the wrong settings, it quickly becomes a hammer akin to propaganda used by those with malicious intent to inflict their ideas on others via power, and that is not considered ethical nor critical analysis. This concludes this series on deconstructivism. I hope you enjoyed it. Until next time …

Derrida, Jacques. (1988). “Derrida and difference.” (David Wood & Robert Bernaconi, Trans.). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. (Original work published 1982).