Deconstructing Deconstructivism: Part III

In this post, I jump back into the rabbit hole known as deconstructivism. Let me begin with this statement: the process of deconstruction is not the opposite of anything, but instead, it is a means of instability. This one statement will color everything else in this post. This much I know—deconstructivism is prevalent in our culture. It perceives any control or order outside of itself as detrimental, unnatural and as a threat to itself. It is built to attack all of this for the sake of its own preservation. A word of caution before reading this post … it is longer that usually and that is due to jumping into the world of philosophy. In that world, language’s importance cannot be understated. It is the primary tool through which philosophical thought is communicated, analyzed and debated. I do not plan to go down into the depths necessary to adequately explain language’s importance to philosophy, but I do plan to dig a little deeper than normal. So, let’s get started.

When discussing deconstructivism or any other philosophical theory, the role of language must be addressed. Language is a communication system that involves words and systemic rules that organizes those words for the purpose of communication. We need language but so does philosophy and its theories. Language, as one of the main forms of communication, is important to philosophy, but before we get into why we need to understand the configuration of language. Language, as a form of communication, has specific components; two of the most important ones are a lexicon and a grammar. A lexicon refers to the words used by the given language. These words have meaning which must be understood to communicate. The grammar is a set of agreed-upon rules used by the lexicon to convey meaning. Without an agreed-upon lexicon and grammar, all communication would be ineffective. Therefore, language is used by philosophy as vehicle of change to deliver its theories and communicate them; deconstructivism, however, took this idea to another level, as we shall see. Over the next several paragraphs, I hope to accomplish two tasks. First, I hope to address how deconstructivism delivered this change, and second, I hope to address the change that was delivered.

How does deconstructivism deliver change? You have probably already presumed that language was involved in some way, and you are correct. Deconstructivism, like all other theories, uses language as means of delivery, but deconstructivism does something no other theory has done … it goes beyond using it for communicative purposes and challenges its authority, or its grammar, by way of tension. It posited that the natural state of language was not fixed or absolute but unstable and fluid. This one fundamental belief does a lot of heavy lifting for deconstructivism. It provides a posture of change in both the lexicon and the grammar of language. Most philosophers assume a prejudice of general language to justify creating their own language. There are many reasons for this; some pure; some not. My point is that when they do this, they assume control of the language and the power associated with it. Deconstructivism is similar in approach but different in scope. It did create some of its own language, but it did this to control all of language. Language is its means of delivering change, but unlike other theories, the scope of change extends beyond its theory and to all of language and culture. It sought to position itself to be the lexicon and the grammar of all language for the purpose of culture coming under its control. How did it do this?

It began with an attack on norms. Any past or pre-established norm was considered a threat to deconstructivism due to stability. Deconstructivism posited that stability is not a norm’s natural state but is, instead, a sign that a norm has moved away from its natural state of instability. The first battle began with language. Is there any bigger norm out there? If it could deconstruct language and re-create it in a way under its control, then, nothing was out of its reach. Culture, in many ways, is defined by its norms, and there is no other factor as impactful as language. We may quibble over whether it is a norm or not, but it does color the culture in which it lives. Norms along with language are two of the standards that define culture. If we understand this, we may better understand some of the political battles taking place and why the fight is so intense. What is at stake? The answer is our norms. They define our culture, and they define us.

Norms are norms because they are behaviors or mindsets considered acceptable by most people of a specific culture despite their own individual beliefs. Norms that are stable define our culture and define who we are, but stable norms are under the constant attack of deconstructivism for one simple reason: stability threatens deconstructivism. Why? We only need to go back to the first paragraph and remember that deconstructivism is not the opposite of anything, but instead, it is a means of instability. Norms that are stable produce consistency, sameness and constancy. Stability is often seen as the opposite of change, and when it comes to human behavior, stability is seen as the neurological basis for consistent habits which involve the stabilization neural information. Stability makes change more difficult, and it makes control next to impossible. For deconstructivism to impact culture, it needed instability to be a norm and then it had to become “the” norm of all norms. How did it do that? It created cultural instability and then became the stability in the instability. Establishing instability as the natural state of language allowed language to be the vehicle of change. It was language that did the work of deconstructivism; it was language that delivered instability to culture.

Deconstructivism still had to address those norms that were most dominant. Deconstructing any norm requires the general population of the culture in which it lives to embrace the change. Support for a change to something stable will only be accepted if there is initial suspicion of the norm. This suspicion flows out of the instability of the norm, which would have been established by deconstructivism. When a tried-and-true norm is perceived as unstable, our human condition takes over rendering us suspicious of it. We begin doubting it and the other norms associated with it. You have experienced it over the last several years … removing statues of past leaders, attacking the integrity of institutions put in place to protect and serve and even promoting bias and oppression as good. This is how deconstructivism delivers the change it needs to live. It has changed you and me, and it is fundamentally changing culture.

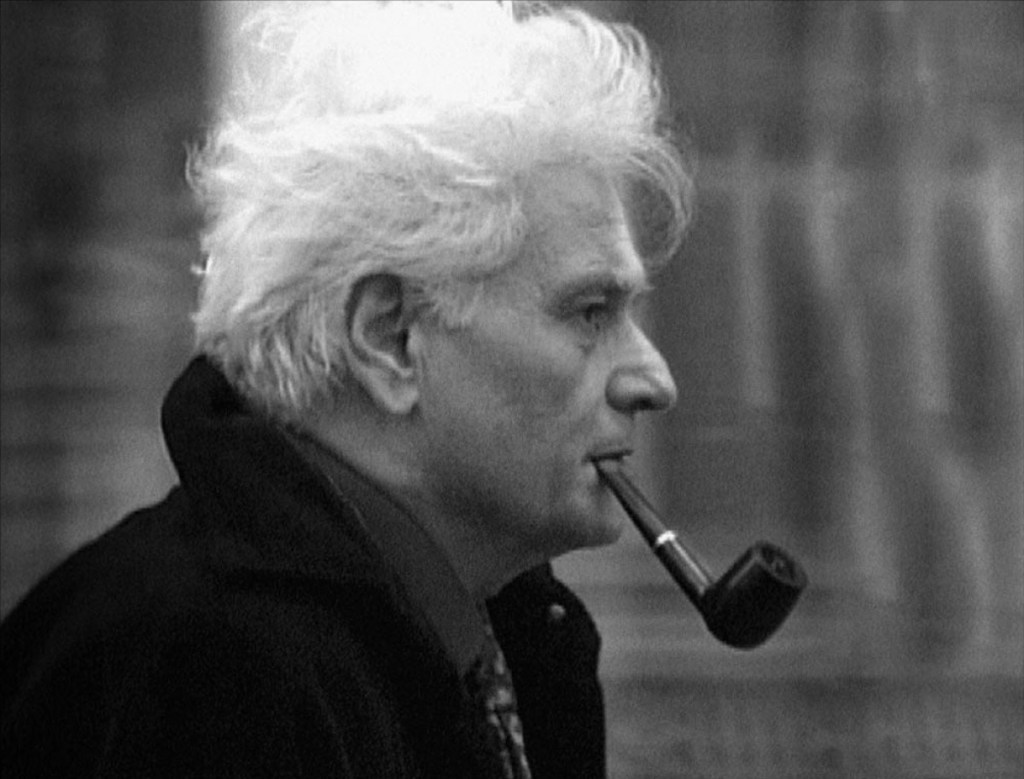

What change has deconstructivism presented as normal? That one is easy; it is instability. Instability comes in many forms. It is tension and doubt. It is skepticism and isolation. What do these things do to us? Well, they weaken our foundations and punch holes into our existing norms, reducing everything to its lowest form, which makes us doubt everything. When we do this everything is vulnerable to the dominant idea of the day, which would be, you guessed it, deconstructivism. Norms are not just commonly held beliefs; they are guard rails of the highway we call culture. Removing them does not bring freedom but danger. A culture without norms was what Derrida wanted because he wanted deconstructivism to be the guard rails of culture. He would call such a state the “absence of presence” or the “already-always present,” and he would embrace it because it would be a culture of instability. Derrida would refer to such a situation as “trace” and see it as a means of stripping away the “supposed” contradictions of language, opening it to new “true” meaning. He would call it “the absent presence of imprints on our words and their meanings before we speak about them” (Jackson & Mazzei, 2012, p. 19).

This is deconstructivism in its truest form. It is “the norm” that defines all other norms by pushing every other one to instability while it remains as the lone stable dominant norm. We see and experience it every day. It is present in our media and especially in our government. If you listen, you will hear it. Truth is no longer that which is true, but that which is repeated and situational. Any belief in anything stable is to be challenged because everything must be unstable. The media is no longer the watch dog of the people but the mechanism of manipulation and change. Anything presented as an absolute is attacked, viewed with suspicion and perceived in negative ways for one simple reason: it is a threat to instability. Then, there is suspicion—we have become suspicious of everything. This is the impact of deconstructivism.

Suspicion is only a short path to the cliff of paranoia. Those who are suspicious of everything eventually doubt everything, which is a form of paranoia. What do you trust in culture? What do you know to be true in culture? Are you concerned that there are no longer real answers to these questions? This is deconstructivism. It works by giving everyone access to itself through suspicion brought on by instability. Someone said to me, but we have community, don’t we? We are told that we have community, but what we really have is isolation. Our “community” is no longer in-person but one of technology. We text, tweet, post and email more than we talk in person; that is not community. That is living inside instability and calling it other things: individualism, preference, perception and self-preservation. Make no mistake, these are not elements of community but elements of instability and deconstructivism.

This world of deconstructivism is a strange world. It is a world where everyone is king. The problem is that when everyone is king, no one is king, except the one who made everyone king. We embrace and encourage selfishness. We no longer talk about integrity and honor. Difference is a means to an end, and we have eviscerated any idea of excellence by calling it intolerance. Everyone has become a judge without ever looking in a mirror. Integrity has been pushed aside and replaced by self-preservation and empathy for others has evaporated into the air. Hard work is viewed with suspicion and all forms of submission are labeled as oppression. We choose criticism over encouragement, negativity over positivity, selfishness over selflessness and materialism over minimalism. This is our world. How are we to respond to it? That is for another day and another post. Until then …

Derrida, Jacques. (1988). “Derrida and difference.” (David Wood & Robert Bernaconi, Trans.). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. (Original work published 1982).